The Government’s first annual progress report on its flagship 25 Year Environment Plan (25 YEP) since it was published in January 2018 has highlighted progress in setting up the post-Brexit framework in which more detailed future policy and actions will depend. But it is far from finalised as yet.

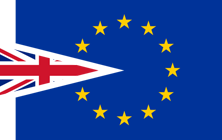

One factor holding back progress, acknowledged in the report, has been Brexit itself, which has led to temporary but large-scale diversion of resources and staff into other policy priorities. This delay has led to concerns the UK’s environmental framework will not be ready in time for Brexit, ushering in a period of heightened risk.

Published on 16 May and covering the period January 2018 to March 2019, the report bears many of the hallmarks of an upbeat departmental update rather than independent assessment. For example, it claims to have delivered 90% of all its 25 YEP objectives for the first year, though it is far from clear how this was assessed. But even so the report and supporting documents provide valuable insights into the direction of policy.

Overall, Defra claims the Government "has taken important steps towards transforming environmental policy", and while there are large differences of opinion among environmental campaigners and professionals over the future direction of policy development and over the detail, there is no doubt a transformation of environmental policy has begun, at least on paper.

Perhaps most significantly, particularly in view of the threat of a post-Brexit environmental policy vacuum, the first year has seen publication of the first Environment Bill in 20 years, claiming to put "environmental ambition and accountability at the heart of government". This has in turn led to intense debate over the robustness of the future governance regime, in the shape of the Office for Environmental Protection (OEP), including concerns over its lack of independence and over whether it will have control of and access to adequate resources to fully carry out its functions. Most stakeholders still believe the new system, at least as envisaged, will inevitably be weaker than the current one backed by EU regulations, leading to an undertaking by Defra to back it with statutory powers.

These debates are still playing out as the Environment Bill undergoes Parliamentary scrutiny, the final outcome still unclear as yet, though environment secretary Michael Gove has shown some willingness to respond to concerns raised.

Meanwhile, the European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018 and secondary legislation made under it is intended to port all existing EU environmental law into domestic law, ensuring the Act continues to operate effectively after Brexit, it claims. The report adds that 13 affirmative and 15 negative Statutory Instruments using the powers in the Act to plug deficiencies in legislation as part of the Environmental Regulations programme.

These instruments cover areas such as waste, air quality, water, and protection of habitats and species, "amending legislation to correct references to EU legislation, transfer powers from EU institutions to domestic institutions and ensure we meet international obligations". Despite this, the process is highly complex, and fears remain of unintended consequences.

But from a practical perspective, one of the most tangible aspects of the emerging plan has been the new indicator framework published alongside it, making the UK "one of the first countries to establish such a comprehensive environmental indicator list from which to monitor environmental progress", including natural capital trends.

Data are still lacking for many of the 66 indicators, organised in ten broad themes related to the goals in 25 Year Environment Plan. One solution it suggests is to engage the public in a citizen’s science project to help fill the gaps, now under consultation with the Natural Capital Committee, though it is hard to see how greater use of scientific expertise can be avoided.

Another key policy is that of biodiversity net gain, consulted on in December 2018, and intended to ensure no net loss, so that new homes and infrastructure are "contributing to ecological recovery and enriching the quality of local greenspaces". The policy, which will shortly be enacted as mandatory through the Environment Bill, already features as a key aspect of sustainable development in the updated 2018 version of the National Planning Policy Framework. It will have fundamental implications for future housing schemes.

Alongside this, DEFRA has also consulted on a new conservation tool for mainly private landowners known as a conservation covenant, placing restrictions on land use changes that could damage biodiversity in return for payments.

Under the theme of "public money for public goods", Defra has introduced an Agriculture Bill into Parliament "that allow us to introduce a fairer, more sustainable system after almost 50 years under EU rules". The legislation aims to pay farmers for their work to protect the environment and provide other public goods, replacing the current subsidy system that pays farmers based on the total amount of land farmed.

DEFRA says that out of the 40 priority actions that are expected to contribute the most to the ten goals of the Plan, four have already been delivered. A further 32 "are on track for timely delivery", with the remaining four actions subject to minor delays, "primarily due to resources being temporarily redirected to support our preparations to leave the EU".

The government also says it has "made progress in laying the foundations for the delivery of targeted actions that will tackle some of our most significant environmental problems", though it is a moot point as to whether all of these are strictly related to the 25 YEP and additional or whether many of them would have been necessary anyway without the advent of the plan. This is because, perhaps inevitably, the plan has become a portmanteau, indistinguishable from the wider range of current and proposed activity within Defra and its agencies.

One such case is the Government’s Clean Air Strategy, which it says "sets out ambitious plans to cut air pollution through a more coherent regulatory framework and stronger powers for local authorities to control major sources of air pollution". This came about due to ongoing failure to meet EU air quality standards, and has undergone several iterations due to its inability to satisfy the European Commission and to several successful High Court challenges by environmental campaigners.

A high-profile area of continuing concern is plastic pollution, notably in the oceans and the need to minimise waste. Actions have included a ban on plastic microbeads, and plans to ban plastic straws, cotton buds and stirrers, as well as extending the 5p plastic bag charge, and introducing a new tax on packaging using less than 30% recycled material. Calls for deeper cuts in single use and other plastic use nevertheless continue to grow.

Defra has also published a comprehensive Resources and Waste Strategy "as a blueprint for eliminating all avoidable waste and doubling resource productivity".

A major area of concern to environmental quality and natural capital is the availability of clean and plentiful water, prompting a wide range of actions from different stakeholders. Water companies have collectively committed over £5bn for the next five-year period to enhance the water environment, a National Policy Statement for water resources infrastructure is to streamline the planning process for nationally significant infrastructure projects, and Defra has overseen a water conservation report in Parliament which endorses incremental leakage targets through water regulator Ofwat building up to a 15% target for water companies by 2025.

Defra has also launched a drive to tackle unsustainable water abstraction through modernisation of licensing. Water quality has been enhanced over 1,700km of the water environment, it notes, and new farming rules tackle diffuse water pollution from agriculture.

The Government also launched the major Glover Review into the future of National Parks and Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONBs). It "strengthened protections for ancient woodlands, veteran trees and other irreplaceable habitats in the revised national planning policy framework", which also helped to resolve earlier concerns over inappropriate use of biodiversity offsetting promoted in the framework. A Fisheries White Paper and the first Fisheries Bill in 40 years also explore how to achieve sustainable fisheries.

Internationally, the UK has consulted on plans to create 41 new Marine Conservation Zones, protecting some 12,000 sq km of marine habitat in UK waters, and has supported plans by Ascension Island for the designation of over 150,000 sq m of its waters as a Marine Protected Area.

Other initiatives include a much tougher ban on ivory, and a new global review of the economic value of biodiversity by Professor Sir Partha Dasgupta. The government has also been working with partners to improve people’s access to and engagement with nature, promoting tree-planting, park enhancement and a wide variety of other smaller initiatives.