In this chapter of Environment Analyst's Corporate Guide: Accelerating your ESG transition, WSP's Ashwini Arun, Daniel Socha, Emily Binning, Gabrielle Brazzil and Ninvita Khoshaba detail how to supercharge your social value.

Introduction

The "S" in ESG is rapidly rising to prominence. At its heart is a need to ensure a just transition as we seek to respond to the climate and biodiversity crises. This chapter explores how an organisation can maximise the social value it creates, and how it can identify ways to measure, improve and communicate that social value with its stakeholders.

What is social value?

Social value is an evolving concept without a single or universally accepted definition. Broadly, it represents the value that an organisation contributes to society beyond direct objectives or profit, and how organisations enrich communities and the lives of the people within them through their day-to-day activities. Organisational efforts to effectively measure and manage social value should aim to create net positive impacts on community wellbeing over time.

Social value is increasingly being used as a lens to address past social and environmental injustices, manage current inequities, and empower communities to participate in environmental decision-making to build healthier, safer, greener, more resilient and prosperous communities. Within the current sustainability and ESG discourse, the concept of social value challenges organisations and businesses to integrate social and environmental justice and equity into all decision-making, programmes and strategies.

Social value is a core principle for aligning with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and through which organisations and companies can design and execute meaningful ESG strategies, programmes and reporting. Incorporating the principle of social value into business fosters integrated thinking that creates bigger impacts for society and long-term organisational success.

The indicators or measures used to evaluate social value are multiple, and vary depending on the project, activity and community, but are typically based around core themes including environment and climate change, sustainable economic growth and employment, health and wellbeing, and inclusion and equal opportunity.

Growing momentum

Efforts to address social inequity have seen renewed momentum with the strengthening of the sustainability and ESG agenda over the past two decades, in response to growing global challenges. But it has only been in recent years that we have started to see the social aspects of ESG rising to the same prominence as the environment and governance aspects.

Increasing emphasis on social aspects has been reinforced by the need to tackle the world’s most pressing environmental and climate challenges in a way that is fair, inclusive and leaves no one behind. For example, there are growing calls that, to be meaningful and effective, the transition to a low-carbon economy must be a just transition.

Social value-related legislation, regulation or policy has already been adopted by governments in several regions, mandating in some instances the inclusion of a minimum social value component in public procurement decisions. For example, in the UK, Procurement Policy Note 06/20 sets out that all central government agencies must evaluate social value with a ‘minimum overall weighting of 10%’ for the total procurement. This ensures that social value considerations encapsulated under the five themes of the UK Government’s Social Value Model are incorporated into procurement activities. Other nations are taking similar actions, such as Australia’s proposed launch of a national ‘wellbeing framework’ in 2023, aimed at assessing progress on a range of social and environmental indicators alongside traditional economic measures.

Even ahead of regulation, public sentiment is driving the private sector to make social value a business norm, as has been the case with climate action and sustainability commitments. Many corporations are hardening commitments, practices, supplier requirements and internal policies to mandate social value management.

Business imperative

From a business perspective, for many, social value has shifted from a ‘nice to have’ to a ‘must have’; there are clear benefits for organisations that integrate social value into their strategies and business practices, both for mitigating risks and creating opportunities.

A strong social value ethos not only drives employee engagement, boosting retention, it can also help organisations attract future employees and potential investors. More broadly, integrating social value into business decision making and strategy can lead to improved relationships and links with communities, fostering stakeholder support and a stronger social licence to operate. To effectively drive business value through social value, it is imperative to communicate transparently in a balanced way.

From an operational perspective, social value also interweaves with numerous corporate functions, including HR; diversity, equity, and inclusion; procurement; early careers; ethics & compliance; corporate real estate and IT. A robust approach to social value not only enhances and focuses these corporate functions but also ensures that they are primed to record data to validate claims. Furthermore, emerging regulations, such as the EU’s Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive, are likely to mandate the assurance of many social indicators.

Organisations that embed social value into their operations strengthen not only the communities around them but equally themselves

Maximising social value

Fundamental to uncovering and maximising social value is recognition that every community is unique, each with its own, particular social context. Social value impacts, risks, and opportunities will vary significantly between communities, and as such, organisations and companies must manage social value by means of bespoke approaches that incorporate the perspectives and voices of each community. For example, the day-to-day challenges faced by underinvested and underserved Black communities in the US could differ markedly to those of Indigenous communities in Australia whose lands overlap with mining activities.

It is crucial to engage and collaborate with stakeholders that will be impacted by a project or activity, and, as part of that engagement, to shift power and decision-making, and ultimately ownership, to the community. This will ensure that the full range of local issues — social, economic and environmental — and the community’s needs and priorities are reflected from the outset.

With an in-depth understanding of the locality, a social value strategy can be formulated to match a specific scenario or project, with a defined vision including objectives and actions, and how they will be delivered. The strategy must be embedded for the entire activity duration or project lifecycle so that the emphasis is on longer-term outcomes not short term deliverables.

Once a project has started, ongoing communication and collaboration with stakeholders on progress and key milestones is critical to encourage further dialogue so that adjustments can be made to maximise the opportunities. After completion of a project or activity, sharing case studies and lessons learned will ensure broader improvement in creating social value and mitigating adverse social impacts.

Measuring social value

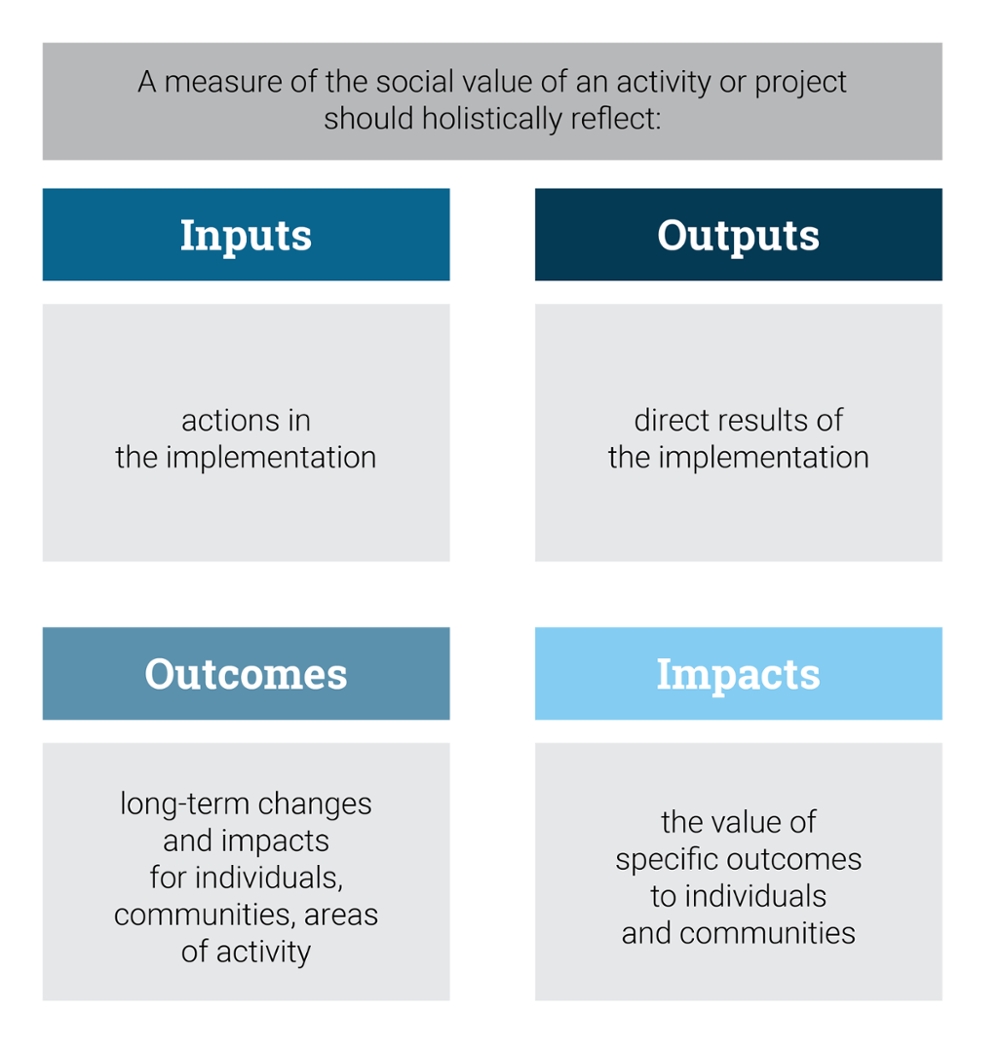

Measuring social value can help identify goals, initiatives and targets to set, to maximise the potential for positive change with the resources available. Measuring social value also brings accountability. However, given that social value is often qualitative and subjective, measuring it can be challenging.

Fundamentally, to measure social value, organisations need both quantitative and qualitative metrics. Faced with hundreds of different social value metrics, it is crucial to choose those that are relevant to a project, and that will generate insightful figures that can be externally validated to avoid the risk of ‘social washing’.

There is a growing market for social value measurement frameworks and tools, some tailored for specific sectors and/ or regions, to help quantify, assess and report social value metrics. Many are designed to map to UN SDGs, or align with emerging social value standards, wider ESG frameworks and national sustainability standards.

Monetising social value

Organisations can apply financial proxy values specific to an activity to demonstrate social benefits and costs. Proxy values are indicative financial measures of the social, economic and environmental impacts of an organisation, specific activity or project. Proxy values are formulated by individual social value frameworks, for example the UK’s National TOMs, incorporating metrics based on fiscal values.

Monetising social value demonstrates to a broad range of stakeholders the scale of any project and how money is being invested and/or reinvested back into local communities. This can help support long-term economic initiatives but also address short-term challenges, such as the cost-of-living crisis. In the UK, applying financial proxy values is already widespread in procurement processes where central or local governments use social value to maximise their purchasing power and secure as much benefit as possible for their local area.

Additionality

Social value is often inherent in the services and activities that organisations provide. For example, commercial involvement in the construction of a new hospital, wind farm, or transportation system brings benefits for society, environment and the economy, and hence generates social value.

It is important to consider additionality, i.e., how organisations can create social value above and beyond normal operations, by choosing different ways of working. Additional social value can be generated by any organisation both internally for its own employees and externally through its activities in communities and supply and value chains

In the UK, WSP has set itself the goal of generating £120m of additional social value over three years by 2024. This will be generated within its own organisation (e.g., staff volunteering; early careers; Equality, Diversity and Inclusion; health & wellbeing) and externally across the community (e.g., apprenticeships/STEM activities, working with local SMEs through its supply chain, donating laptops, humanitarian aid).

"Fundamentally, social value is about improving people’s lives by asking them what they need and making it happen. It requires a mindset shift from doing less bad to doing more good. And measuring corporate social value is an important part of driving that shift." Emily Binning, WSP UK, director, corporate ESG.

Social value takeaways

It is inevitable that social value will continue to crystallise as a business and organisational norm, just as health & safety has been for decades, and more recently climate mitigation and resilience.

In April 2023, a new global Taskforce was created to consolidate the efforts of the Taskforce on Inequality-related Financial Disclosures (TIFD) and the organisations preparing a Taskforce on Social-related Financial Disclosures (TSFD) into a single initiative.

The aim of the new structure is to develop a global framework for financial disclosures around social- and inequality-related risks and opportunities. Following on from, and integrating with, the Task Force on Climaterelated Financial Disclosures (TCFD) and the Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures (TNFD), this new taskforce will harmonise social value reporting into the wider ESG sphere in the future.

For many businesses, operationalising and reporting on social value considerations represents a new challenge.

Case study: Cape Breton Island is a former coal-mining, steel-making town in Nova Scotia, Canada. The local economy was heavily impacted by the closure of those industries thirty years ago, with numerous knock-on effects for the population.

A new health centre and school had been planned for the community, but Build Nova Scotia wanted to extend the project’s original remit to generate wider opportunities for students and community. As such, Build Nova Scotia expanded the project with the aim of enhanced social value creation.

Community members were closely involved throughout, from deciding what facilities it should offer to how the facilities were designed. The New Waterford Hub will include a school for children aged 11-18, a community wellness centre, a health centre and a long-term care home.

The students will have access to onsite medical facilities, for themselves and their families, and the opportunity to gain work experience in a healthcare environment.

"There’s a huge community spirit in New Waterford, and we want to engage with that to improve those determinants of health. Hopefully when we look back in 15 or 20 years, we’ll see that we’ve made a difference to people’s lives." Mickey Daye, clinical director, Nova Scotia Health

Conclusion: getting started on social value

- Secure organisation-wide support for incorporating social value into data gathering and reporting activities.

- Examine where and how your organisation may already be generating social value; engage and clearly brief different stakeholder functions, giving them time to gather the data.

- Explore different frameworks/platforms that can focus your organisation or corporate measurements; pick metrics to enable, rather than restrict, what you evidence and measure; develop a roadmap that will see decisionmaking powers and ownership shifted to community leaders.

- Measure themes that are relevant for the project and/ or community; ensure data is credible and stands up to scrutiny.

- Examine the data and gaps, and use them to highlight opportunities, inform action, and make adjustments to improve strategies/plans.

- Report the real outcomes of your actions, i.e. the stories behind the impact you have created, which can often outweigh the numerical assessment.

This chapter of Environment Analyst's Corporate Guide: Accelerating your ESG transition was kindly authored by Ashwini Arun, project director, sustainability, energy and climate change; Daniel Socha, global sustainability and ESG services lead; Emily Binning, director, corporate ESG; Gabrielle Brazzil, assistant vice president, equity center; and Ninvita Khoshaba, social value lead — at WSP (www.wsp.com).